This subject has a deep fascination for me both as history and as a practical art. This attempt at a more long form post hopefully works and I will be coming back to it when I can with new research, results of practical experiments and other readings.

Reading Craig Barron and Mark Cotta Vaz’s (1) great book about matte painting has revealed to me the interesting genesis of the optical printer starting with several strands.

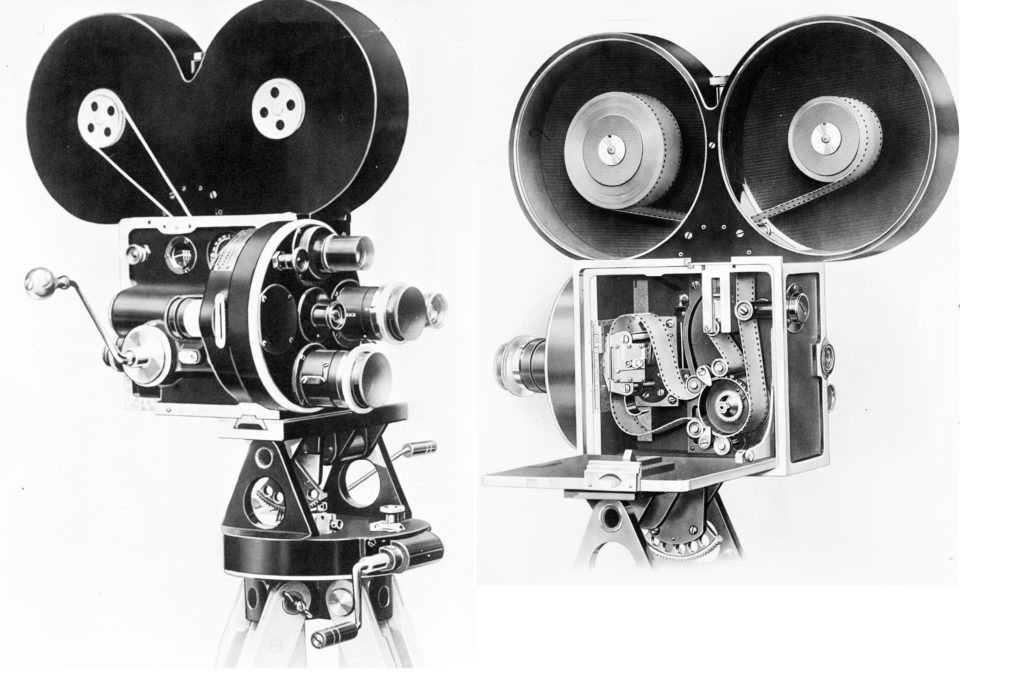

Starting with Norman Dawn and going through to Clarence Slifer we see the emergence of the requirement for such a machine out of the relation between the camera and its own optical system under the condition of projection, that is when camera negs are projected with the taking lens. (this process later on came to be called Rotoscoping).

Slifer built a system to composite the matte work in Gone With The Wind (many mattes in that film) and Norman Dawn discovered early the benefits of the registration properties of the Bell and Howell 2709 camera in terms of composite tolerances necessary for the ‘original negative’ matte to work. (A technique he felt he’d invented enough to try and patent it). This process liberated the artist from the labour intensive and location bound ‘glass shots’ which were done in camera.

After Dawn developed the idea of taking the painting control into the studio he effectively required the camera and projector to form some degree of combination or symbiosis or at least altered the projector enough for it to take on some characteristics of the camera, namely single frame registration and light control. So in some ways the optical printer emerges as a specialist function of the projector, a kind of ‘Camerafication’ and this idea is confirmed by Salt, B (2009) below.

In some ways then the location glass shots were an enaction of the camera, being in the moment and the present. Wheras the act of taking into the studio was a way of thinking with the camera. Planning ahead in time knowing certain things and conditions would occur if certain actions were taken in advance.

Another thought is how mattes at this time were always static, wide, establishing shots (not always of course) that formed part of the emergence of film grammar. In that space of solid, framed and held, earthed, locked and perhaps even architectual visual space, the optical printer had its freedom/chance to develop. The foundational bases required for buildings finding another application in the large and heavy metal bases needed for optical printers. In another way the optical printer is a machine linked to the environment! It is rooted upon the ground which it relies on for its operation.

(note: see Katharina Loew’s talk at the DOMITOR 2020 online conference about early cinema split screen effects. https://domitor2020.org/en-ca/split-screen-effects-and-early-cinema/ . Such a good talk and I was thrilled to see so much mention of mise-en-abyme that has been occupying my ideas since writing my MA dissertation. )

Whats interesting then to me is how closely the development of matte painting techniques occurs in parallel with the optical printer. The changes brought about to make matte paintings work better had far reaching effects for all areas of special photographic work.

Also the cost dimension, as in the fine engineering design and fabrication associated with say the 2709, was still effecting results as late as when Pop Day was still using a Debrie to make his own orig’ neg’ matte paintings for Elstree with a young Pete Ellenshaw looking on. (we talking late 1920’s here…) as well as new technologies like fine grain film which came along in time to allow something like King Kong who had the master Linwood G. Dunn doing opticals, the eventual designer (with others) of a kind of standardised optical printer configuration.

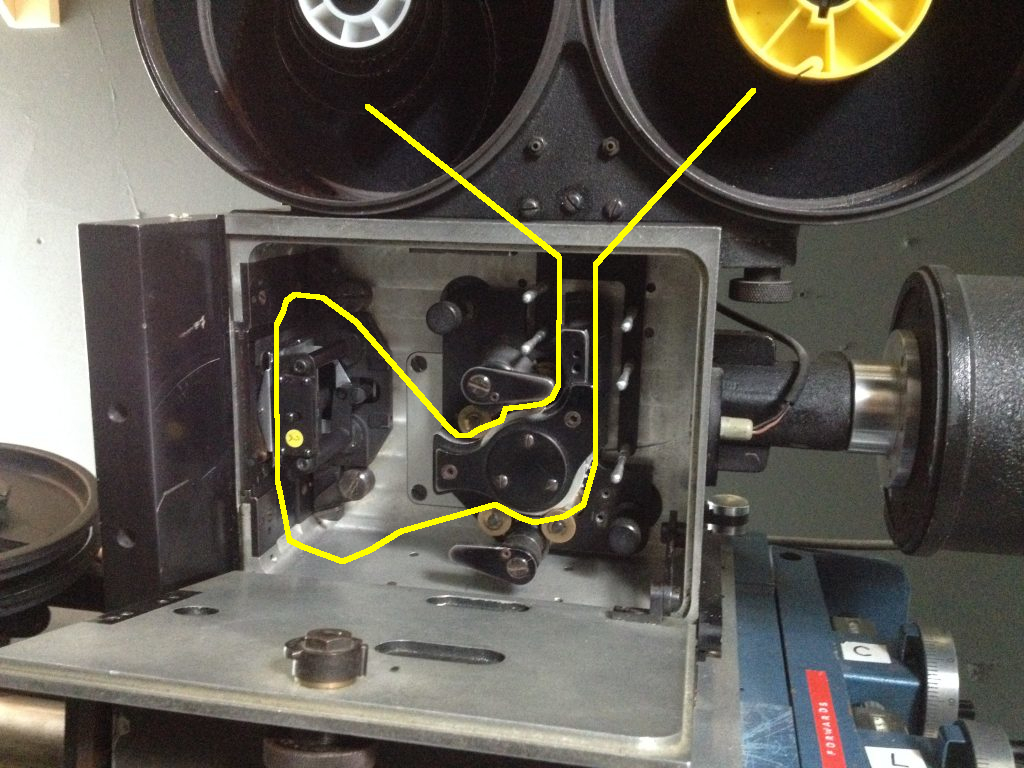

I cant be sure until I have examined a 2709 (2) closely but there is a distinct similarity to the film path in an Oxberry animation camera. I’ve heard this story about Oxberry getting into trouble because they copied the B&H movement. In the 2709 illustration above the gate looks very similar. In the blog linked below by Adam Wilt there are some good photos of the camera being loaded and gate being oiled.

Infact, cinemagear.com list this ‘B&H type’ shuttle for the 2709 (converted to VistaVision) as opposed to Acme type shuttles so perhaps the oxberry gates would fit a 2709?

Its also hard to ascertain how fast you can crank the oxberry, shuttle and fixed pin type gates and my training always stipulated 12fps as a guide plus in its setting on printers or rostrum stands it was always a single frame camera. Having said that, my oxberry, when driven by the Deimos controller in reverse, rewind basically, goes at one heck of a speed. Another factor are modern polyester stocks which you would not want in there at that speed. How brittle was new nitrate stock?

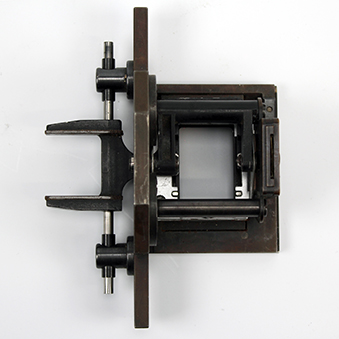

There is much in all this that could guide practical experiments. For instance using a Debrie to make experimental glass and orig’ neg’ matte shots and seeing for myself the ‘jiggle’ and if this property could be put into the service of other ideas, ie non-illusionistic. Also designing a system for projecting processed material (instead of using the cameras) by adapting and machining the two pin & claw type gates that Lew Gardener gave me. These are like half oxberry, half mitchell style shuttles. The registration is done with a fixed pin but the transport is done by a pivoting claw. Theres a 16 and a 35.

Another area or question is ‘which kind of gates was Linwood Dunn using in his designs?’

https://www.oscars.org/film-archive/collections/linwood-dunn-collection-0

notes

(1) The Invisible Art. The Legends Of Movie Matte Painting. Craig Barron and Mark Cotta Vaz. 2002, Chronicle Books, San Francisco.

(2). If anyone wants to gift me one of these cameras they have two at cinemagear.com. one for $9000 and one for $6000. Ha ha!

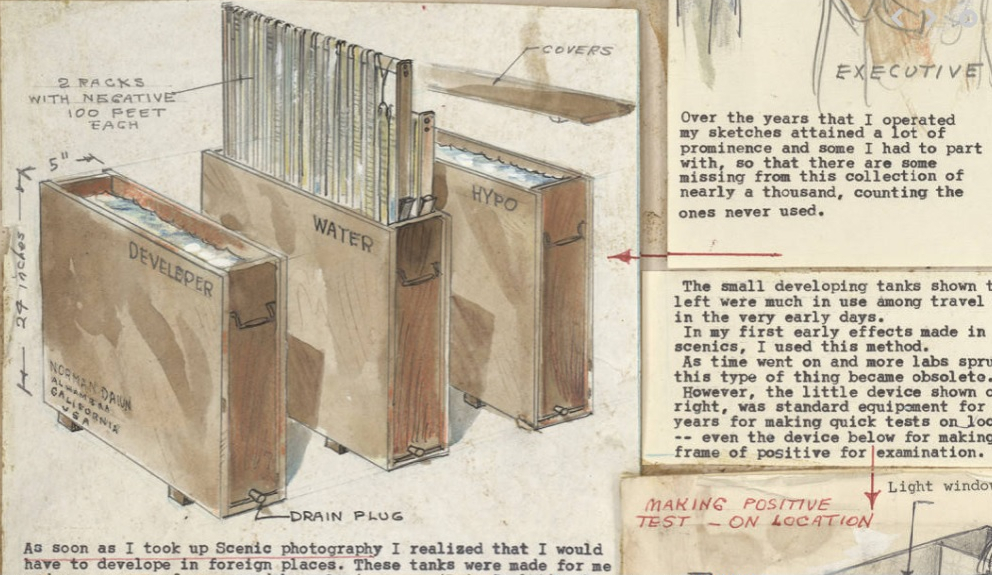

Explore the Norman Dawn collection below. Of main interest is his use of the Debrie (Missions Of California) and the timeline on his move to the B&H, ie what are the records relating to other uses of that camera in Hollywood at that time? His ‘Cards’ at this collection are a real treat and I recommend anyone into film now, artists, film makers and all those hipster analogue youngsters to look at them. Even things like these processing boxes are interesting. I mean if I wanted to make some, did they have plywood then? And all this was being done often out in the hot sun with nitrate stock!! In the card I have enlarged below there is even a tiny test contact printer. (Card 1). This great resource can be found at the Harry Ransom Centre at the University of Texas.

Salt, B mentions (p186) in period 1920 – 1926 leading figures as Irving Knechtal and Max Fleischer. On p51 he mentions the process being called ‘Projection Printing’ although he offers no citations or references for this. Need to look further into this.

Further reading (link to external blog/material. I hope none of these people mind me linking this way. They’re really good blogs. )

Any serious matte fan will already know this blog below and Im posting it here incase you havent discovered it. I’d love to get in touch with with NZpete actually as he seems like a one man treasure island!! Just endlessly incredible research…

http://nzpetesmatteshot.blogspot.com/2010/06/jack-cosgrove-burning-of-atlanta-from.html

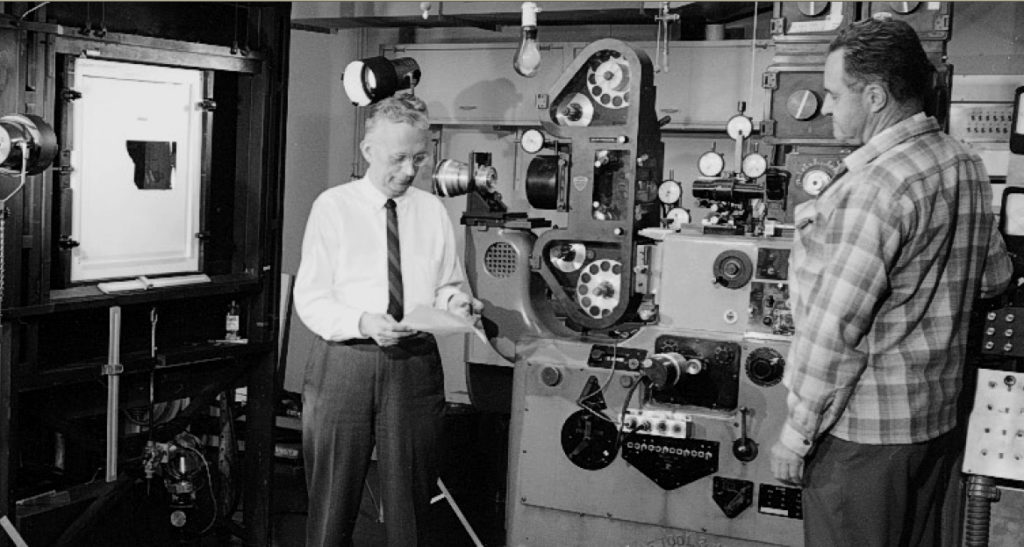

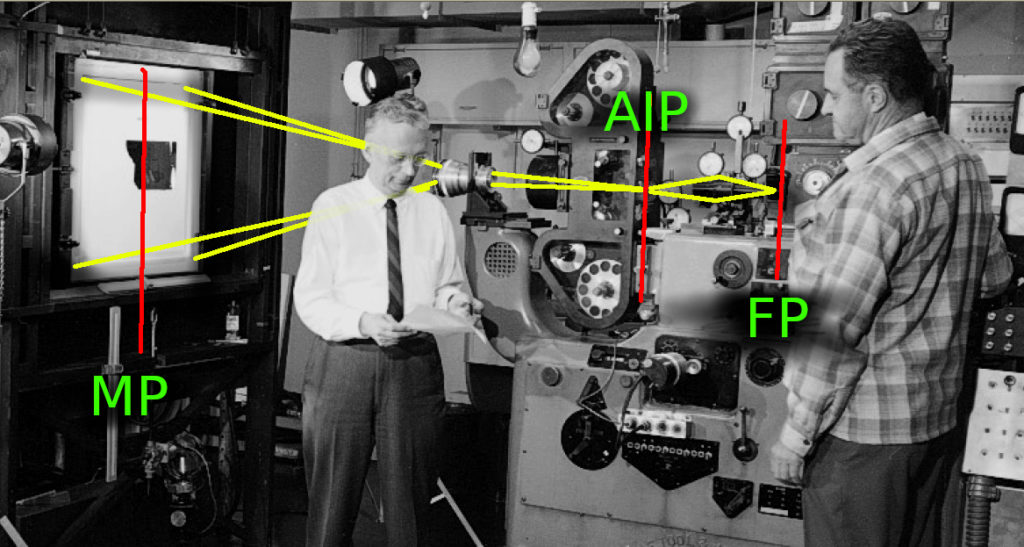

Lastly, Ive copied this photo of Clarence Slifer here (on left) from NZpete’s blog about optical effects because it shows something quite important. Its especially important to me because it might dictate the next stage of my own studio practice. The optical printer in this photo has been arranged so that with a suitable printer head, a further plane, distant from the main printer base can be imaged. This plane is of course here one occupied by a matte painting, the square area on the left lit up. In almost every setting Ive seen optical printers in, they do not allow this as everything re-photographed is considered film based.

This arrangement could theoretically ‘expand’ the functionality of a printer to include flat artworks or even small sets. I’ve experimented a bit with flat art work that is mounted between the projector gate and camera, but here we have a real sense of how the optical printer is more a studio camera than anything else.

Here is my decoding of what is going on here. MP is a matte plane which is brought to focus by the lens just next to Slifer onto AIP, aerial image plane. The AIP can be checked by inserting a gauze, or ground glass. Additional exposed film elements are threaded into the reels seen above and below the AIP. If one of these film elements is a filmed live action foreground with masked out background, ie black and the MP painting fits this masked area, then they come together at AIP. The MP focussed by the lens, the film element sitting in the same plane. The final film at FP film plane images them both via its lens. This whole thing could be done with another mask in the bi-pack magazine seen behind Slifers assistant Dick Worsfold’s head. This mask could hold back another pass made later of another/different matte painting.

Below is a photo I’ve found in Raymond Fieldings comprehensive focal guide to special effects cinematography. It shows the same type of printer config as above but interestingly Fileding does not mention Slifer anywhere in this book. Below is a further photo showing clearly what happens in the aerial image system as opposed to normal optical printing.

What is apparent then is that an aerial image, although not visible to the eye unless diffusion material occupies the image plane, is, nevertheless, imaged again by the next lens which is the one here in the camera gate. If there is a film (already shot and exposed and developed) in the projector gate, they will combine together, but in what kinds of ways?

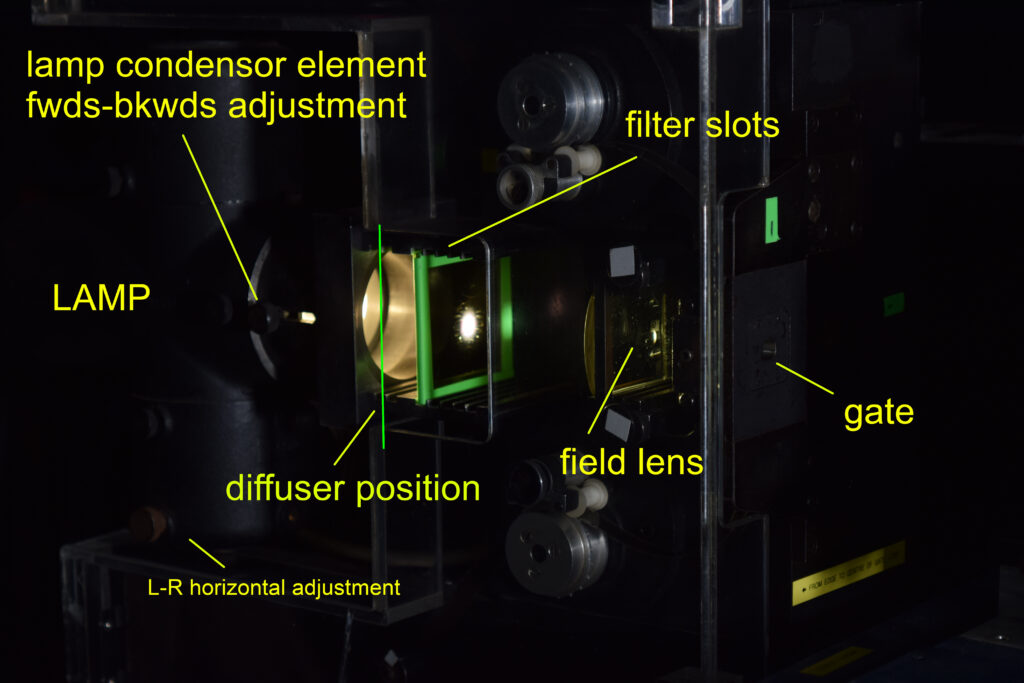

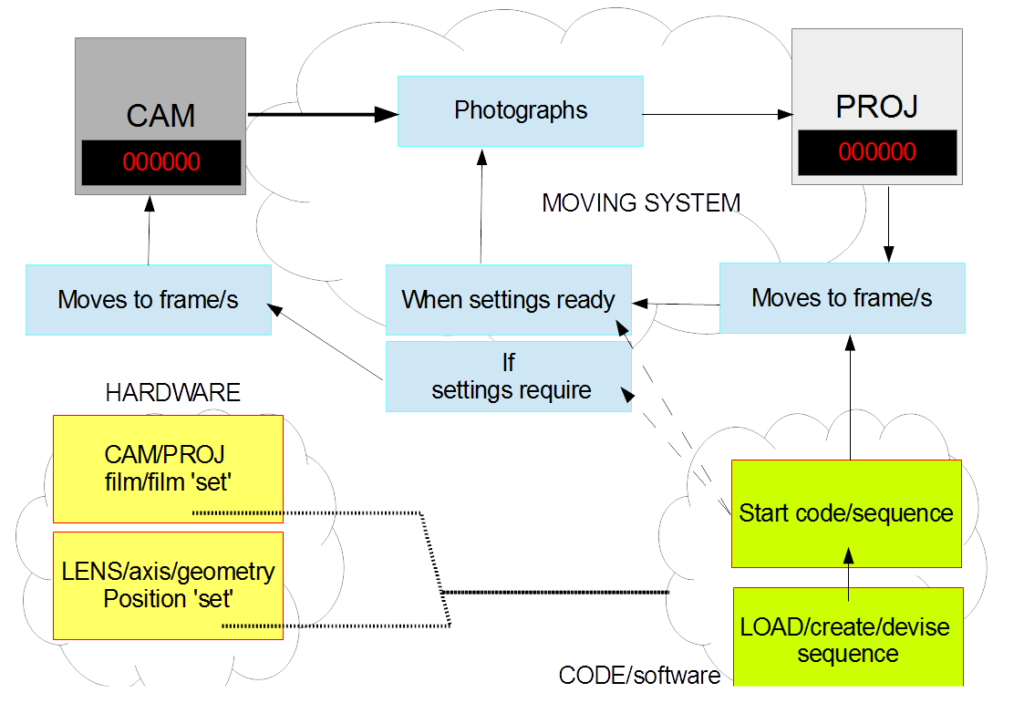

As a guide to my own practice trying to reconfigure and modernise (digital controls) optical/contact printers, here is a state of operation diagram that shows the functioning basis of this machine. There is only one counter for PROJ’ ECTOR because my system is a single head, that is there is only one gate for holding exposed film material to be rephotographed. There is much to be said for modernising these machines mainly because the electrics they were built with are old, unreliable, hard to find parts for, and don’t offer nearly as many functions as modern micro-processors.

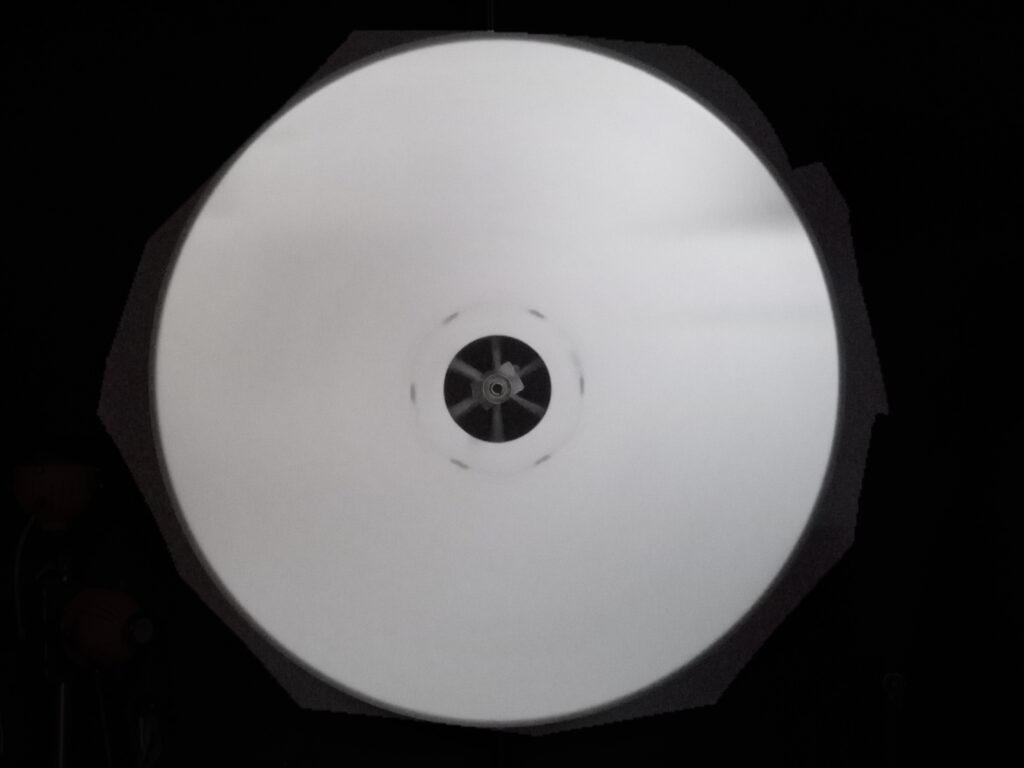

Another area of fruitful research has been ‘patents’ that relate to different technologies and techniques in the printer. For example here is a patent entry from 1977 that goes into detail about using diffused light as opposed to collimated in optical printers. It mentions the possibility that with well set up diffused light and exposure variables, results can be as good, if not better that those achieved in direct contact printing. This detail has significant implications for analogue film restoration let alone production possibilites.

Another direction entirely is the use of optical and contact printers by artists, or film makers that would be better contextualised as not part of commercial narrative cinema. This whole area has not really had any significant work no doubt due to the diverse, unrecorded, adhoc, home-made and personal nature of some machinery but also because commentary or writing on experimental cinema has a tendency to focus on the politics of the image or aesthetics rather than too deep a tangential exmanination of specifc techniques or apparatus.

Cinema Journal, Volume 57, Number 4, Summer 2018, pp. 71-95 (Article)Download

There maybe good reasons for this however I myself can’t but help be interested in what exactly Yervant Gianikian and Angela Ricci Lucchi’s ‘analytical camera’ looks like or how it works as well as numerous others including Pat O’Neil, Jordan Belson, etc. It would be easy to argue that under the control of artists the optical printer has developed into a different kind of instrument that brings into question problematics in perception and representation that have had far reaching impacts in contemporary moving image culture.