Dear Walter Murch……

I have been thinking recently about the, perhaps deeper and more long term meaning of Nachleben, prompted by reading your new book and seeing the error in your calculation about how much time during an analogue film presentation you spend in darkness.

You say, with justified confidence (page 29 – 30) that “For a 2 hour film, you spend 1 hour in darkness“. (Suddenly Something Clicked , Faber 2025).

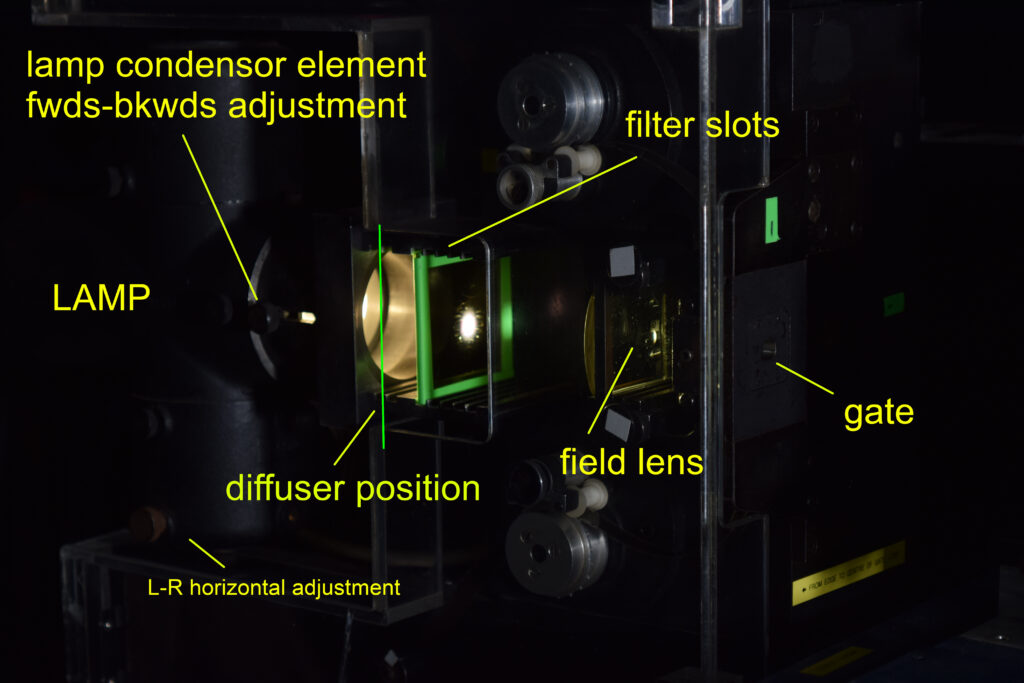

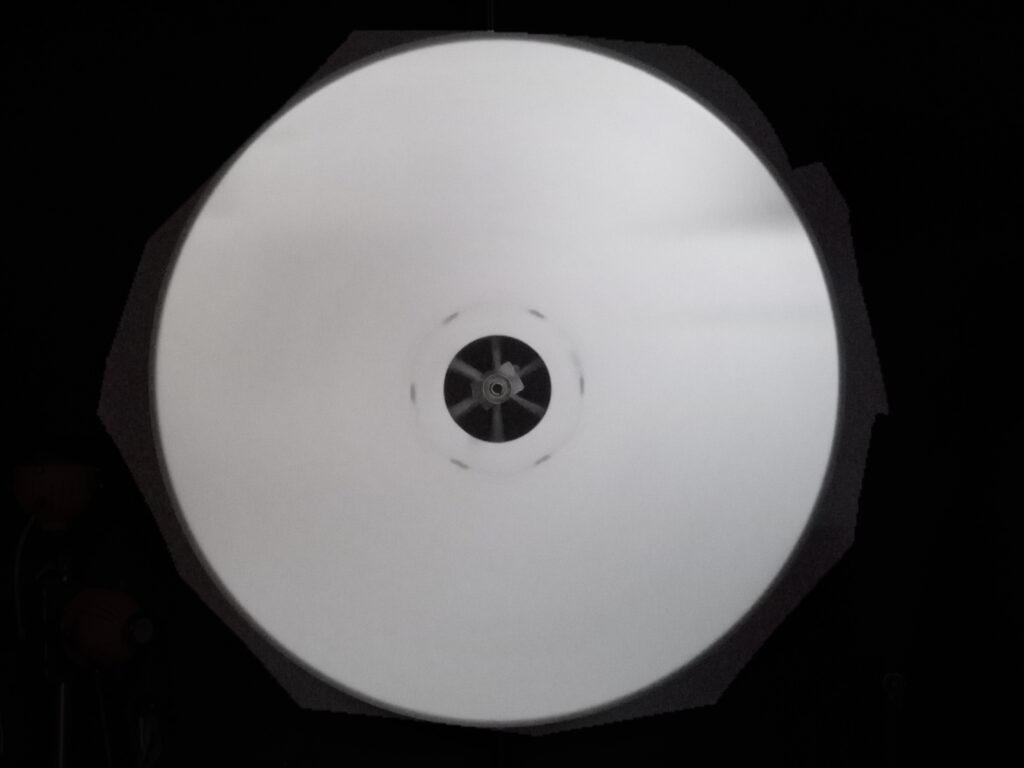

Now its easy to see the mis-calculation. You have looked at a film projector blade and seen 3 openings and closings. You then thought, well each frame is projected 3 times, so 3 x 24 = 72. This is partially right. There is a basic image frequency flicker of 72hz on a 3 bladed shutter BUT, and for me this BUT is a BIG BUT, you have made the incorrect assumption that those shutter blade sections are equal when infact they are not. They will almost certainly have a proportion in terms of light and dark of 3:2.

No I am entirely happy to be wrong. Perhaps all cinema blades are made unequal. Perhaps you could show me the projector type and make, photograph the shutter for me and we can measure it. Better still, lace up some 35mm and film the screen with a decent hi-speed video camera. Then in an edit programme, count the blacks and the images. I bet $100 the ratio will be 3:2? (BTW, have you tried this with a DCP projected, uuugggh! Its ugly, not what you think it will be).

This is a minor detail. I mean, in a 2 hour film you spend either 1 hour in darkness or 48 minutes! Who cares? In a totally honest way, it only matter to me because of one very critical issue. That is what Nachleben is, after all, an attempt at investigating, the AFTERLIFE of film and how and in what ways in SURVIVES, and in this case “what even was it in the first place?”

Its a shame because your book, if full of insightful glimpses into science and related technical fields to cinema such as the ross Cache, should be held to as high a standard of empircal accuracy than any other form of scientific research? It feels a shame you couldnt find my research as all the calculations as we read them on page 103, where the error of equal light/dark shutter openings is repeated might be wrong, or better, slightly inaccurate.

You even mention in a foot note somewhere that theres no reason why the dark phase of a cinema projector shutter couldn’t be incorporated into a digital or digitised film. Well, you might find if you tried this operation that equal light and dark openings modulating at a fixed rate like 48 or 72 hz would produce image sequences that would not match mechanical ones. This is what lead me to the realisation that the base count is 5. As you could read in other posts, this count is based on solid empirical study of cinema projector blades/shutters. There needs to be 5 frames for every 24th of a second which means the frame rate, to achive a standard 24fps needs to be 120fps!! Only recent SMPTE DCP standards do support 120fps, so maybe I should make a flickering DCP and see if anyone can screen it.

This is calculated like this. Each 24th of a second digital file needs 3 pictures and 2 blacks. The pictures are up on screen 60% of the time, the dark is up 40% of the time. The whole thing, all 5 frames needs to change 24 times a second. 24 x 5 = 120.

Cinema and ratios have a rich history. We would stand to be corrected if we said we shot a film in 1.84:1. We would be wrong is we said academy was 1.35:1. Ratios define the cinema frame, composition, historic development and technical standardisation. I’m just saying ratios define what is pleasing, what works, what provides the best light/dark balance.

My argument, that analogue cinema follows a human centric paradigm is nicely supported by a 3:2 ratio. Read this AI response for instance to the question; Cultural significance of 3:2 ratio?

The ratio 3:2, while seemingly simple, holds cultural significance in various fields, including music, visual arts, and architecture. It’s closely associated with the concept of a perfect fifth in music, as well as the Golden Ratio, which is considered to have aesthetic value in art and design. The 3:2 ratio also finds application in photography and printing, particularly in aspect ratios.

Music. Perfect Fifth: The 3:2 ratio represents the interval of a perfect fifth in music. This is a fundamental musical interval that is considered consonant and harmonious.

Hemiola: In early music theory, the perfect fifth was also known as a hemiola, indicating the relationship between the frequencies of two notes.

Just Intonation: When strings are tuned to the exact 3:2 ratio, the resulting sound is smooth and consonant.Visual Arts and Architecture: Golden Ratio Approximation.

While the Golden Ratio (approximately 1.618) is different from 3:2, it is often seen as a harmonious proportion and is sometimes approximated by the 3:2 ratio in art and architecture.

Aesthetic Value: The Golden Ratio and its approximations have been used by artists and architects throughout history to create visually pleasing and harmonious compositions.Classical Architecture: Examples of architecture utilizing proportions related to the Golden Ratio include the Parthenon and the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Photography and Printing: 3:2 Aspect Ratio: The 3:2 ratio is a common aspect ratio in photography, particularly for 35mm film and digital images, as well as for print sizes like 6″ x 4″. This ratio is widely used for printing photographs, ensuring a natural-looking aspect ratio.

In essence, the 3:2 ratio, while not as prominent as the Golden Ratio, still carries cultural weight in various domains, particularly in music and aesthetics. It’s a simple ratio with complex cultural implications, reflecting human understanding and appreciation of harmony and balance.

So, this ratio has been with us for a long time. Im not saying someone said lets put a 3:2 ratio of light and dark into film projection shutters because it gives film or cinema a cultural weight. Rather Im saying we arrive at these proportions when we are in tune or in balance with ourselves, with nature. Nature here being our perception, our comfort, what feels right.

And we can see, in early cinema shutters and how they developed over time, that there was destined to be a final point where the amount of light hitting the screen HAD to be tempered by A) the mechanical necessity to pull down the frame, which itself had to be masked, and B) any flickering produced by this interaction. At some point, someone, somewhere arrived at a good balance point. Around 48hz picture flicker rate, with light dark in a 3:2 ratio.

(NB, its funny you mention 3 bladed shutter as in my experince these are quite uncommon).

The digital erasure of the mechanical properties of analogue projection is what started me on the path that lead to the truth of light/dark ratios in cinema shutters. To recap, any digital moving image of born film material will erase, or write out, or ignore, or prosaically destroy, the effect that mechanical delivery will create. So, if we want digital to recreate, or preserve or conserve, or mimic this effect how many frames of black are there compared to how many frames of image?

Read all about it here, if you got any spare time. I think you might be impressed by the 1/1200ths of second fade in/out that the slicing action of the shutter produces.

Further research

“Effect of Gate and Shutter Characteristics on Screen Image Quality”, Willy Borberg, SMPTE Journal, October 1957, Volume 66, pages 623-627 (from FILM-TECH list, yet to find this online)

https://academic.oup.com/edinburgh-scholarship-online/book/22094 could be interesting but currently lingering behind academic fortress.